506th Fighter Group - Mustangs of Iwo

In The Closing Months Of Hostilities, Seventh Fighter Command's P-51s Were To Fly The Longest Combat Escort Missions of WW II, And Do It On A Routine Basis!

AIRPOWER, Volume 7, Number 1, page 30, January 1977

By Barrett Tillman

When General Curtis LeMay first dispatched his 20th Air Force B-29s from the Mariana's in November 1944, it was out of need rather than convenience. The bomber command had moved to the Mariana's from China because logistical problems on the Asian mainland were immense. Despite China's closer proximity to the enemy's home islands, supplies trickled in so slowly, that it took weeks to stock enough materiel to mount a worthwhile mission. Though the Mariana's lay 1,500 statute miles south of Tokyo, requiring very long range missions almost entirely over water, the supply problem was much simpler, and by late 1944, the U.S. Navy owned the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco to Subic Bay.

THE ISLAND

Once the B-29s began operating from Saipan (MAP) and Tinian, little time was lost in extending the USAAF's reach northward. It took only one brief glance at the map to see why the Volcano Islands, as they were called, were the next target for U.S. Marine conquest. Lying 790 miles due south of Tokyo, they presented a perfect mid-point emergency field for stricken B-29s. But more than that, they put Japan within range of the ubiquitous North American P-51 Mustang, WW ll's escort fighter par excellence. With the Volcano's in Marine hands, B-29s could receive fighter support anywhere over southern Japan.

Actually, only one of the three tiny islands which comprised the Volcano's was suidiv for airfields. As the name implies, the group is of volcanic origin and each island is covered with sulphuric ash. The composition of the Volcano's is such that two of them are named North Sulphur Island and South Sulphur Island. The one in the middle is simply Sulphur Island—Iwo Jima in Japanese.

In February, 1 945, the former pair were steep, rugged and uninhabited; they had probably never supported human life. But Iwo Jima itself was different. It had a flat plain the middle, between 556-foot Mount Suribachi to the south and a lengthy bluff, some 380 feet high, over most of the north end. This plain held three airfields, numbered one to three from south to north, though the latter was far from completion. Some 21,000 Japanese diehards defended this island, and not even the heaviest bombing or shelling could dislodge them.

In February, 1 945, the former pair were steep, rugged and uninhabited; they had probably never supported human life. But Iwo Jima itself was different. It had a flat plain the middle, between 556-foot Mount Suribachi to the south and a lengthy bluff, some 380 feet high, over most of the north end. This plain held three airfields, numbered one to three from south to north, though the latter was far from completion. Some 21,000 Japanese diehards defended this island, and not even the heaviest bombing or shelling could dislodge them.

On February 19 the first half of the Third, Fourth and Fifth Marine Divisions' combined 70,000-man strength went ashore on the southeastern beaches. The intensity and viciousness of the fighting is too well known for recounting. Suffice it to say that when Iwo was declared secure nearly a month later, on March 16, one-third of the assault force had become casualties: 23,200 in all, of which 4,554 were killed or missing. As Iwo Jima is eight square miles in area, it had taken about 2,900 Marine casualties per square mile to capture the island. Only Tarawa in the Gilberts was more costly, yard for yard, in the entire Pacific War. Nor was little Iwo as secure as the Americans believed, for about 3,000 Japanese remained alive, hiding in underground caves.

Yet the invasion of Iwo Jima began paying off almost immediately for 20th Bomber Command. On March 4, nearly two weeks before the island was considered captured, a B-29 named "Dinah Might" set down on the southernmost airfield, which was being renovated by the Navy's Sea Bees. The B-29 pilot, Lt. Fred Malo, had taken his Superfortress to Tokyo, but very nearly ran out of fuel because the auxiliary tanks could not be used. Malo's was the first of some 2,400 emergency B-29 landings on Iwo Jima.

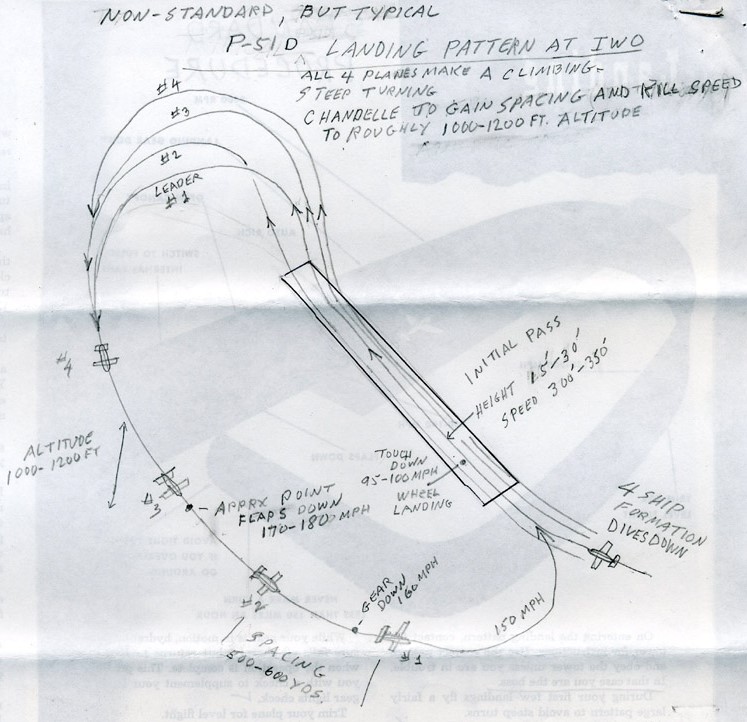

Drawing supplied by Ed Linfante, 462nd

Displaying the 3 airfields of 1945

No. 2 was the primary field for the B-29's & No.3 North Field the home of the 506th Fighter Group

>

>

Two P-51 groups were ready to move into Iwo just as soon as facilities could be readied for them. The Mustang's seven-league boots were legendary in the European Theater, where the war was almost over, as Eighth and Ninth Air Force P-51 s easily flew from southeastern England to Berlin and back, nearly 1,200 statute miles. A few 1,500-mile shuttle missions from England to the Ukraine had also been undertaken, but once P-51s were based on Iwo they would fly round-trips of that distance as a matter of routine.

>Planning for these Very Long Range (VLR) escort missions had begun in July 1944. Though the Mustangs would be directly involved in support of 20th Air Force bombers, they remained under the jurisdiction of Seventh Fighter Command—the "Sunsetters" — named after their seven-rayed Japanese sun insignia. Directly responsible for the Iwo Jima fighter operation was a 37-year-old West Pointer, Brigadier General Ernest M. Moore. One of the AAF's young flying generals, "Mickey" Moore was an experienced fighter pilot who had been in the Pacific since 1939. He had joined the Seventh Air Force shortly after Pearl Harbor and was promoted to chief of 7th Fighter Command in August 1944.

The 15th Fighter Group comprised of the 45th , 47th and 78th Fighter Squadrons was the first to arrive at Iwo Jima, via Hawaii and Saipan in February. The group landed on Iwo's southern field (Number One) on D-Plus 15, March 6, with General Moore touching down in the first Mustang.

The 15th Fighter Group comprised of the 45th , 47th and 78th Fighter Squadrons was the first to arrive at Iwo Jima, via Hawaii and Saipan in February. The group landed on Iwo's southern field (Number One) on D-Plus 15, March 6, with General Moore touching down in the first Mustang.

Eleven days later the first elements of Colonel Ken Powell's 21st Fighter Group landed on Airfield Number Two. The 21st included the 46th , 72nd and 531st squadrons, and had seen prior combat in the Southwest Pacific. But most of the pilots were new, averaging about 250 to 300 hours total flight time, with the exception of the squadron and flight commanders, who averaged close to 1,500 hours. Nevertheless, the group was brand-new to the Mustang, having traded in its P-38Ls for P-51 Ds in December and January.

Iwo Jima was crammed with airplanes—two P-61 night-fighter squadrons, Navy and Marine strike aircraft and assorted Army and Navy sea-rescue planes. But the P-51s were the most numerous and strategically the most important. They broke in slowly, the 15th F.G. first flying dawn and dusk CAPs beginning March 7—a boring but necessary duty. Enemy aircraft were extremely rare, and only got through on three occasions— once in May and twice in June—but they caused little harm.

Before taking up the ambitious VLR escort and interdiction missions, the P-51s began eliminating airfields, shipping and ground facilities in the Bonins, 125 to 150 nautical miles to the north. Strikes against these islands, Haha Jima and Chichi Jima, would continue til the end of hostilities, for although they had to be neutralized, they were not worth the effort of capturing. The Bonin Islands flights tended to be milk runs; in five months of operations against them, the Sunsetters lost only two aircraft to enemy action.

Unlike the captured or bypassed islands elsewhere, Iwo Jima was in the front line of the war; in fact, it was the front line. But that didn't stop General Moore's fighter pilots from establishing the more important features of civilization, which were sorely needed in such desolate surroundings. Capt. Henry Crim who arrived with the 72nd F.S. noted, "Iwo was perhaps the most hostile ground environment an airman could find himself in. Nature provided an active volcano (Mount Suribachi) and man provided the war."

There was literally no place to go, not much to do and precious little to be seen, so once established, the pilots found other means of spending their off-duty time. In the Army flier's search for diversions, the Navy Sea Bees figured prominently. Busily engaged in expanding Airfields One and Two (Number Three was never fully completed), the Construction Battalion sailors' lesser known motto was, "We'll do anything for whiskey." When it was discovered the Sea Bees had an ice machine but no booze, and the fighter pilots had plenty of "liquid green" but no ice, the laws of supply and demand took over. The 21st F.G. traded 15 bottles of whiskey for an ice machine, including installation cost. Dug in, sandbagged and camouflaged, the precious device escaped detection by the irate Sea Bee skipper, until General Moore assumed the duty of island commander. After that, the fliers had nothing to worry about.

Next on the Mustang pilots' schedule was a structure officially described as a "briefing hut." Actually it was a pretty fair club, the first building was built in one day by 50 pilots and featured fresh running rainwater, a bar, a refrigerator, indirect lighting, a band stand, screened windows and a battleship linoleum floor. Most of these items were obtained from the intrepid Sea Bees, enjoying a flourishing ship-to-shore business with the aviators, who traded more whiskey for Coca-Cola and beer. The ebb and flow of inter-service commerce flourished right up to V-J Day, and one Mustang pilot recalled, "When the war ended we had enough supplies to last us for another year, and all the materials and equipment to build a swimming pool, including a concrete mixer."

"Ye Olde Iwo Jima Spa." Probably the only reason the swimming pool wasn't finished was an establishment called "Ye Olde Iwo Jima Spa." A brainstorm of the 21st Group's flight surgeon, the spa was actually a bomb shelter converted to more civilized purpose. Metal wash tubs, rubdown divs and piped-in hot water from underground sulphur springs were installed. A supply of beer was arranged, which allowed pilots to debrief after each mission with a mineral bath, a cool brew and a rubdown. "It really took out the kinks and probably added to the embellishment of mission accomplishments," recalled one pilot. "Man, it made flying a pleasure."

Left to their own devices, the formidable alliance of Sea Bees and Mustang pilots may have eventually turned Iwo Jima into the world's unlikeliest health resort, but the war still forced its attentions upon the men. However, Iwo's environment had the peculiar effect on some pilots which made them more attentive to the job at hand. Harry Crim was one who shared this opinion.

An aggressive Floridian, Crim was one of the more experienced fighter pilots on Iwo. He had flown a full 50-mission tour in North Africa, Sicily and Italy with the 14th F. G. in P-38s. After the sand, flies and disease of Tunisia, where he lost 50 pounds, Crim became something of an Iwo booster. He believed that 100% concentration on combat, with no serious diversions, was one of the island's strong points. He helped his pilots devote full-time attention to flying and fighting, thus preventing them from going "rock-happy."

THE MUSTANG

Thirty years after the war, General Moore would recall: "I don't believe there is any question about the P-51 being the best prop fighter of WW II. It was our top air fighter, and hence best for escort missions, and equal to the "47" as an attacker against ground targets." Squadron and group commanders were just as enthusiastic, describing the sleek North American as "perfect for these missions." Unlike the P-47 groups on le Shima in the Ryukus, which began operations in May, 7th F. C. Mustangs could loiter for over two hours in the Tokyo area, as le Shima was 200 statute miles farther from the Japanese capital than Iwo.

But the pilots of the 15th and 21st groups were not particularly well experienced in the 51. Both groups had received their first Mustangs in late 1944, and between shipment from Hawaii and staging through the Central Pacific on escort carriers (Kalinin Bay), there had been little time for extensive transition. Most check-outs were done in the Marianas, and by the time the groups arrived at Iwo, probably not even the senior pilots had 50 hours in the Mustang. In the 21st , for instance, the more senior pilots averaged 20 hours in the P-51 before reaching Iwo, while the majority of the pilots were newly out of operational training units and averaged only a mere five to ten hours in 51s.

Major Harry Crim of the 21st group's 531st squadron was an exception. A veteran, with 2,200 hours total time, he had logged 35 in the P-51. It was enough to become well acquainted with the Mustang's characteristics, though Crim still favored the P-38 from his Mediterranean tour.

In the Pacific, it was the Mustang's long, lean legs which made the difference. In the ETO the normal drop tank was of 110-gallon capacity, but for the VLR Pacific missions 165-gallon external tanks were more often employed. Fully loaded, two 165-gallon tanks added a ton to the Mustang's 10,100-pound "clean" combat weight. But they allowed an hour or more over Japan, depending on power settings, as opposed to only 20 or 30 minutes on internal fuel. The larger externals also added longitudinal stability to offset the crucial weight-and-balance problem posed by fuel sloshing around in the fuselage tank.

With such heavy takeoff loads the Mustangs needed a good long run, even at sea level. When completed, Airfield Number One had a 5,000 and 3,900-foot runway; Number Two's were 5,200 and 4,400 feet. Originally, however, these runways were barely 2,000 feet and thus hardly adequate for B-29 emergency landings. Quite often they were altogether too short. Following a typical large mission against Japan, 50 to 70 Superfortresses in all manner of emergencies stopped at Iwo rather than risk the extra 800 miles to the Marianas. "The 29 drivers did a wonderful job of getting their crates on the ground, but some really catastrophic accidents were inevidiv," recalls Harry Crim. "At first Airfield Number Two was only an emergency field, so we got some desperate boys. Our coffee tent on the flight line was wiped out three times before we got smart and moved it to the upwind side of the runway."

On another occasion a B-29 lost directional control, ran off the runway at about mid-point, churned up a mound and crunched down in the 531st's maintenance pocket. The Boeing's wings broke down and the fuselage cracked in the middle so the nose and tail both drooped. "The result looked like a mother hen sitting on her chicks because five of my 51s were under it," Crim sadly recalls.

The Iwo Jima groups had augmented squadrons, with 37 Mustangs and 57 pilots, so in most cases only squadron or group commanders had personal aircraft. General Moore had a pet Mustang which, despite his heavy administrative load, he usually managed to fly about 20 hours a month. The standard tour of operations for an Iwo |ima P-51 pilot was 15 VLR missions—about 105 hours flight time— plus whatever local ground support or patrols were required. After the first few VLRs, Moore restricted pilots to no more than six VLRs in one month.

When the 506th F. G. with the 457th , 458th and 462nd squadrons arrived in mid-May, some of the strain of operations was eased for the first two groups. The 506th alternated with the 15th and 21st in making two-group missions to Japanese Empire targets, so one of the three could anticipate a stand-down when the schedule was set. It also allowed more time for crucial maintenance.

The 506th pilots were generally more experienced in P-51 s than their 15th and 21st counterparts. Lt. Neil T. Smith, Jr. of the 458th squadron recalls, "Looking in my old log book, I had about 500 hours of fighter time in P-39s, 40s and Jugs, and another 150 hours in 51's before arriving at Iwo. Probably a third of the pilots in our outfit had that much 51 time, and some had other fighter time the same as I did."

One P-47N group, the 414th under Col. Hank Thorne, arrived in late July but was only active from Iwo for five weeks before the surrender. The yellow-and-black marked Thunderbirds primarily flew ground support, though some missions were made to Japan.

The comment that "maintenance on Iwo was tops" seems universal among the 51 jocks. If a pilot wanted a new carburetor all he had to do was mention it. Many crew chiefs kept their aircraft waxed and sanded for extra speed, though some joked it was because there was nothing else to do on Iwo. The mechanics conscientiously changed spark plugs after every VLR mission to avoid fouling later on, as the prolonged low-RPM cruising from Japan tended to burn up plugs.

Lt. Harve Phipps of the 72nd F. S. recalls, "The maintenance crews were excellent. The squadron had been in the Seventh from the beginning and the crew people were not rotated very often. They were experienced and we had practically no aborts because of maintenance." Pilots genuinely appreciated such hard-working mechanics; the last thing in the world they needed to worry about was engine failure 600 saltwater miles from home.

Weather

Weather

A far more bothersome consideration was the adverse weather between Iwo Jima and Japan. There were usually three to five fronts moving south from the Japanese coast, which made mission planning difficult, to understate the matter. In such a situation, high dense cloud formations had to be dealt with.

The Mustangs seldom penetrated a front, but tried to fly between the thunder-heads at the saddle backs. When possible they would remain in the clear and avoid the worst of the often violent turbulence, for once in it, the 85-gallon fuselage tank became a critical factor. In rough weather "the 51 with the fuselage tank full didn't fly like anything resembling an airplane," Harry Crim said. Standard procedure was to run the tank down to 40 gallons maximum, which put the weight-and-balance on the near side of controllability before entering weather. But even then, it was no fun flying a 51 in turbulence. When the drop tanks were partially empty the gas sloshed from front to rear and back again. Pilots compared the sensation to riding a roller coaster. In these conditions it was almost impossible to fly straight and level under VFR (Visual Flight Rules), much less on instruments.

Sometimes the fighter jockies found themselves on the gauges without warning. Crim was escorting B-29s which took his formation into a light spot of a developed thunderstorm. With his canopy back about three inches for ventilation, Crim was guiding on one Boeing when it suddenly disappeared and his lap was instantly covered with snow. There was only one thing to do: Crim called the squadron to initiate a 180-degree turn, descending at 500 feet per minute. "After what seemed like 20 minutes we were back in the clear. My whole squadron of 16 planes was tucked into the tightest formation you've ever seen. I'd look back a couple of times and couldn't even see my wingman, so I don't know how they flew formation." A second attempt to penetrate on the deck was foiled by driving rain so the mission was aborted.

It was not an unusual occurrence. From late April to late June, 832 P-51 strike sorties were dispatched from Iwo Jima but fewer than half, only 374, reached their targets. Four missions were completely spoiled by heavy clouds, and for ten days in early May the Mustangs were weathered in.

The worst weather problem occurred on June 1 when 7th F. C. dispatched 148 Mustangs, which encountered a solid front from sea level to 23,000 feet. B-29 weather recon planes with fighter pilots aboard preceded each strike, and this time reported the front was thin enough to penetrate. But the 51s hit a severe thunder-head and had no choice but to make an immediate turn out of the soup.

Flying completely blind in extreme turbulence, several Mustangs collided and others fell to the violent winds. Twenty-seven P-51 s were lost, with all but three pilots. The 506th group, on operations only two weeks, lost 15 aircraft and 12 pilots. Finally 27 Mustangs got through to escort the bombers over the target, Osaka. On another mission one lone 72nd squadron pilot stuck it out through the weather to find himself the sole escort for about 400 B-29s!

Operations officers tried to give pilots clear areas over Japan, but even with alternates it was not always possible. Sometimes the 51s arrived over the target area only to find the whole region socked in. The 21st group reached the rendezvous point after one mission only to be told that Iwo was zero-zero, and the pilots were to divert to Okinawa. A quick computation of remaining fuel showed the Ryukus were out of range (about 900 miles southwest) so there was no option but to proceed to Iwo. It was mostly IFR (lnstrument Flight Rules) on the way back, but fortuitously the clouds opened up to 1000 feet ceiling and three miles visibility within ten miles of Iwo Jima. Everyone raced into the landing pattern and plunked down wherever room was available—at one time there were nine Mustangs on Airfield Two's short runway. Several minutes later the weather was zero-zero again. Recalled General Moore, "Believe me, not only were our chaplains praying that day."

The pilots were fond of saying that if there was a cloud in the Pacific, it was always sitting right on top of Iwo Jima. Ground heat and the presence of sulphur in the salt air made Iwo even more prone to cloud formation than most islands, and much of the time the air from sea level to 50 feet was clear but the island itself was fogbound.

For this reason, Iwo received one of the early Ground Control Approach units. It was set up on the main runway of Airfield One (longest on the island), which presented an instrument approach within perhaps 100 feet of Mount Suribachi's northwest slope. "It takes a lot of good-weather practice approaches before you'll trust the thing," observed more than one pilot.

Navigation

Flying single-engine fighters on a round-trip of 1,200 nautical miles over a vast ocean with minimal onboard aids required a fancy bit of navigating. It was a task for which none of the Mustangs and few of the pilots were equipped to attempt on their own. The P-51 Ds had a magnetic compass and instrument panel clock; no radio compass or other nav aids. Voice communication was available by one VHF four-channel radio, and that was all. "You lose your radio or dynamotor and you have to time-and-distance 600 nautical miles to a spot in the ocean less than four miles in diameter," said Harry Crim. "Coming back if your radio worked you could get a steer for the last 100 miles from radar, if it was working. That's why you didn't want to be alone."

Fortunately, help was available. Six B-29 navigation planes, in three pairs, led about 100 Mustangs on each mission to a prearranged spot off the Japanese coast, and circled there while the 51s went inland. As the Mustangs began reaching the rendezvous point the first pair of B-29s waited until about half the fighters had arrived, then set course for Iwo. The other two pair of Superforts departed the coast at ten-minute intervals, allowing latecomers to latch on to one pair or the other. The last B-29 to depart continually transmitted on the "Uncle-Dog" frequency so any remaining straggler could home in.

Seventh Fighter Command frankly regarded Uncle-Dog as the greatest invention to come out of the war. It consisted of a pair of VHF antennae side by side on the 51 's aft fuselage, tuned one-quarter wavelength apart. Whichever antenna got a signal first would transmit to the pilot's earphones and suppress the other signal. The right-hand antenna gave a Morse Code letter U (dit-dit-dah) "Uncle from the phonetic alphabet. The left-hand antenna gave the letter D "Dog" (dah-dit-dit). The pilot then turned in the appropriate direction and refined the heading by watching his compass. When both signals were received simultaneously the pilot heard a steady hum, which meant he was on course for base or for the transmitting aircraft.

Seventh Fighter Command frankly regarded Uncle-Dog as the greatest invention to come out of the war. It consisted of a pair of VHF antennae side by side on the 51 's aft fuselage, tuned one-quarter wavelength apart. Whichever antenna got a signal first would transmit to the pilot's earphones and suppress the other signal. The right-hand antenna gave a Morse Code letter U (dit-dit-dah) "Uncle from the phonetic alphabet. The left-hand antenna gave the letter D "Dog" (dah-dit-dit). The pilot then turned in the appropriate direction and refined the heading by watching his compass. When both signals were received simultaneously the pilot heard a steady hum, which meant he was on course for base or for the transmitting aircraft.

One convenient and major aspect of the navigation problem was the relative bearing of Iwo Jima from Tokyo. The Japanese capital lay between the 139th and 140th meridians, while Iwo was between the 141st and 142nd, a fraction east-southeast of Tokyo. The magnetic variation between Iwo and Tokyo in 1945 was three degrees west, and since—as every student pilot learns—"east is least and west is best," the compass course from Iwo to Tokyo was exactly 360 degrees, or due north. The return heading was straight south, 180. It made dead-reckoning navigation much simpler for the occasions when pilots had to rely on DR to get home.

Nature provided numerous landmarks along the way, in the form of islands and small islet groups, but they were several miles west of the Iwo-Tokyo route and consequently were obscured in any kind of heavy weather. There were six such groups or major islands ranging from 40 to 500 nautical miles north of Iwo Jima, with the first coastal islands 50 miles further north. Pilots were provided with excellent strip maps, well detailed with topological, navigational and tactical information. In some ways they were better than the sectional aeronautical charts which private pilots use today.

AIR-SEA RESCUE

In any sort of long over-water operation such as 7th F. C. was engaged in, an efficient air-sea rescue service was mandatory. Three means of rescue were available to downed fliers: seaplanes, submarines and destroyers. These were code-named Dumbo, Playmate and Juke Box. Destroyers were generally stationed at 100-mile intervals from Iwo to Japan while submarines and PBY amphibians worked in Japanese coastal waters.

CAP patrol over Iwo 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante in a Josephine (click here for explanation) configured P-51. "Pilots were rotated in flying the Josephine on CAP. CAP was confined to a radius of approximately 50 miles around Iwo. The tank was supposed to be dropped at very low altitude (for accurate targeting) to a pilot or other downed person in the water (B-29 crewman, etc.) who may not have had his own infladiv raft. I'm not sure it was ever employed. We always carried an annoying, but necessary, dinghy hung below our butt as standard equipment."

CAP patrol over Iwo 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante in a Josephine (click here for explanation) configured P-51. "Pilots were rotated in flying the Josephine on CAP. CAP was confined to a radius of approximately 50 miles around Iwo. The tank was supposed to be dropped at very low altitude (for accurate targeting) to a pilot or other downed person in the water (B-29 crewman, etc.) who may not have had his own infladiv raft. I'm not sure it was ever employed. We always carried an annoying, but necessary, dinghy hung below our butt as standard equipment."

Memoirs of 2nd Lt. Ed Linfante Pilot 462nd Squadron

Statistics at war's end proved that a downed airman stood a 50-50 chance of being rescued, almost regardless of where he-went down. If he wasn't picked up within a few hours he was almost certainly captured, or he drowned. Therefore, all personnel spared no effort to pluck an aviator out of the water as soon as possible.

The Mustang pilots faced an additional problem. The P-51 handbook warned that the aircraft would float for perhaps two seconds after hitting the water, so standard procedure was to bail out rather than ditch.

Once a man was down in Empire waters, at least one flight "capped" him, orbiting overhead to guide in submarines or PBYs and to disrupt Japanese attempts to capture him. In extreme cases Mustang pilots spent ten" hours in the air on such a mission, abandoning their briefed targets and circling a squadron mate for four hours before heading home. Some pilots recall seeing a submarine within a half-mile of shore trying to pick up a flier. On another occasion two Japanese sub-chasers set out to drive the rescue submarine down and capture the pilot, but CAP Mustangs blew both vessels out of the water. Another time the submarine skipper tired of the game, went in close to shore, sank a harassing patrol craft, scooped up the airman and departed. At one time the 21st group had ten pilots on the duty submarine.

Both B-17s and B-29s were employed as air-drop rescue planes, specially modified to drop large motor boats to B-29 crews or even to a single pilot. Based on Iwo Jima, they circled 50 to 100 miles off Japan until called in. The 531st F.S. watched while one of its pilots climbed into one of these boats only five miles offshore, expecting him to crank up the motor and head out to sea where he could be rescued. But the pilot could not get the motor started, and when the Mustangs finally had to leave, the Japanese came out and took him. Quite naturally, this caused a sensation back at Iwo and all the available boats were checked. "Sure enough, none of them would start," Harry Crim recalls. "Needless to say, boat maintenance picked up after that." One of Seventh Fighter Command's pet peeves was that many new pilots had little or no idea of how to survive in the water. After helplessly watching one of his men drown because he couldn't get out of his parachute harness, Crim and others urged the implementation of a weekly training program which included tossing pilots out of a boat while instructors stood by to demonstrate or lend a hand.

But if some pilots lacked complete survival training, the rescue crews never lacked courage. Responding to a report of a pilot in his raft blowing into the harbor of Chichi Jima, a gutsy PBY pilot splashed down near the harbor mouth and taxied through mortar fire from shore. One of the crewmen jumped from the Catalina into the raft, definitely confirmed the pilot was dead, and only then scrambled back into the aircraft. The PBY turned around and took off through more mortar shells.

It was said that some pilots were so satisfied with the rescue service that they "came back for more." Lt. Frank Ayres of the 15th F. C. limped his damaged Mustang 430 nautical miles back from the first Tokyo mission before he had to bail out over a destroyer. Two and a half months later, after battling three enemy fighters, Ayres hit the silk over a lifeguard submarine and landed so close he didn't even have time to inflate his rubber raft.

The 1500-Mile War

The bare statistics of what was involved in one VLR mission don't begin to tell the story. In round numbers, nearly 100 Mustangs whose 1945 value was a little under six million dollars took off with 57,000 gallons of high-octane fuel and some 230,000 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition. By 1976 standards the fuel alone would cost $46,000.

The round-trip distance of 1,500 statute miles was equivalent to halfway across the North American continent; from Los Angeles, California to Little Rock, Arkansas. Except for the time spent above Japan itself, the entire mission was flown over water in a single-engine aircraft with minimal navigation equipment. Seven-hour missions were routine; eight hours were not at all uncommon.

Most missions involved 96 Mustangs; 48 from each of two groups. The basic unit was the 16-plane squadron flying in four sections of four aircraft each. Three squadrons comprised each group for a total of 48 Mustangs, plus several spares which accompanied the mission 200 nautical miles (230 statute) outbound and replaced any aborts. General Moore often tagged along with the spares, and would have gone all the way to Japan had not his superiors forbidden it.

Takeoff was a time-consuming, often tricky process. The volcanic ash which swirled along the flight line and runways was whipped into clouds by the Mustang's propellers. In no-wind conditions it was sometimes necessary to pull 60 inches of manifold pressure out of the Merlin engines at 2,800 to 3,000 rpm, depending on the engine's governor setting. It was virtually the only condition under which 51 pilots went to 3,000 revs (excepting war emergency power) and none of them liked to do it.

Takeoff was a time-consuming, often tricky process. The volcanic ash which swirled along the flight line and runways was whipped into clouds by the Mustang's propellers. In no-wind conditions it was sometimes necessary to pull 60 inches of manifold pressure out of the Merlin engines at 2,800 to 3,000 rpm, depending on the engine's governor setting. It was virtually the only condition under which 51 pilots went to 3,000 revs (excepting war emergency power) and none of them liked to do it.

Cruise speed and power setting was whatever it took to keep up with the navigation B-29s at the outbound altitude of 1 0,000 feet. Usually this involved 2,300 to 2,400 rpm and about 35 inches, giving an indicated airspeed of 200 miles per hour. The mixture setting was auto-rich, as there was no shortage of fuel northbound, and pilots wanted a good deal of it burned prior to landfall.

Droning along with the navigation planes for a minimum three hours was not exactly fascinating, and many pilots took Benzedrine divts to help remain alert. The more adventurous experimented with the slipstream of the B-29s, seeking a close formation spot which would give them an aerodynamic tow. Eventually the Mustang jockeys found a slot very close to the right blister gunner position, behind the number three engine, which allowed the 51, when properly trimmed, to fly almost locked in place. But the B-29 drivers usually got nervous with a fighter so close and changed the power setting, thereby "ejecting" the Mustang from the slipstream.

Contrary to procedure in Europe, the 7th F. C. Mustangs didn't escort specific bomber boxes, but a long stream of B-29s as much as 200 miles front to rear. One fighter group was assigned target cover, which ran from the Initial Point to the target, and another gave withdrawal support. Usually flying 2,000 feet above the bombers, the three Tar-Cap (Target Combat Air Patrol) squadrons were in trail, 4,000 to 5,000 feet, laterally, from the stream. Two squadrons flew on one side of the bomber stream, one on the other side, with each four-plane flight about a half-mile apart. The three squadrons were thus in a staggered line-astern, flying in the same direction as the B-29s approaching the drop point.

When the first squadron commander reached that point, he called the group and ordered a 1 80-degree turn in place—an aerial "to the-rear march." The trailing squadron now became the lead, still flying above and wide of the bombers, but in the opposite direction. When the new leader reached the IP he called another turn, which put the group back on its original heading. It took about ten minutes to cover the area from IP to target, and the process was repeated as long as necessary. The most likely point of enemy interception was near the IP, so the escort was concentrated in that position, ready to pounce.

Usually flak was the most nodiv form of opposition, but 90-degree course alterations and slight altitude changes allowed the fighters to remain under heavy AA fire for nearly an hour with little or no damage.

Japanese fighter opposition could be fierce and determined but generally the P-51 pilots had little respect for their opponents. The biggest problem was finding the Japanese in the air; few pilots saw enemy planes airborne more than five or six times. Actual engagements were even less frequent. "Our finding enemy aircraft was difficult," Harry Crim relates. "They weren't interested in really tangling with us and the only aggression I saw was when they thought they had you at a great disadvantage. Some of the pilots were skillful but there weren't enough of them to make much difference."

The first VLR mission from Iwo, an escort to Tokyo on April 7, was one of the exceptions. It featured beautiful weather and lots of bandits. The 15th and 21st groups escorted 107 B-29s of the 73rd Bomb Wing and, in the 15 minutes allotted over the target, encountered stiff opposition. Pilots estimated 75 to 100 Japanese fighters were seen, and they knocked down 21 of them for the loss of two Mustangs.

The 15th F.G. saw the most combat that day, returning with claims of 17 destroyed, one probable and six damaged. Major James B. Tapp was "belle of the brawl," tangling with four different types and bagging three. He first damaged a Nick, then shot down a Tony, an Oscar and a Tojo. Harry Crim headed the 21st's score column with two of the group's four kills. He bagged a Tony and a Nick. Tapp and Crim were destined to become two of the Iwo fighter command's five aces, with Tapp the first to achieve that distinction when he shot down a Mitsubishi Jack on April 19.

Ranged against the Mustangs was a wide variety of Japanese fighters. Only Jack had the 51 's speed, and none could match the Mustang's acceleration or high-altitude performance. The most numerous Japanese fighters were the Navy's Mitsubishi A6M line, including the ultimate Zero, the A6M6. The JAAF's most widely-deployed fighter over the Empire was the Nakajima Ki-84 . . . Frank to the Americans. Zeke was about 100 mph slower than the Mustang and could only hope to out-turn or out climb it at low to medium altitude. Among the fastest enemy fighters, Frank was still about 50 mph slower than the North American, but climbed and turned better. Still, a 51 employing combat flap could stay with Frank long enough for a kill, if the Mustang's speed wasn't excessive. Otherwise, Frank would evade with a tight turn when the 51 opened fire.

Ranged against the Mustangs was a wide variety of Japanese fighters. Only Jack had the 51 's speed, and none could match the Mustang's acceleration or high-altitude performance. The most numerous Japanese fighters were the Navy's Mitsubishi A6M line, including the ultimate Zero, the A6M6. The JAAF's most widely-deployed fighter over the Empire was the Nakajima Ki-84 . . . Frank to the Americans. Zeke was about 100 mph slower than the Mustang and could only hope to out-turn or out climb it at low to medium altitude. Among the fastest enemy fighters, Frank was still about 50 mph slower than the North American, but climbed and turned better. Still, a 51 employing combat flap could stay with Frank long enough for a kill, if the Mustang's speed wasn't excessive. Otherwise, Frank would evade with a tight turn when the 51 opened fire.

The Kawasaki Ki-61, dubbed Swallow by the Japanese and Tony by the Allies, was a poor match for the 51; its only advantage was lighter wing loading. But ironically a serious engine shortage turned the Swallow into a falcon. Faced with a lack of the 1,160-hp liquid-cooled engines for which the Ki-61 had been designed, (See Airpower, March 1975) the Japanese quickly developed a means of fitting extra Tony airframes with 2,000-hp radials. The result was a match for almost any American fighter in the war. Designated Ki-100, the radial-engine Tony never received an Allied code name, but was respected by Mustang pilots who suddenly found their speed advantage badly depleted.

But the Mustang's superior high-altitude performance gave it the edge in most cases where the Japanese attempted interceptions. Though the B-29s often bombed below 20,000 feet, the Mustangs were always above the Boeings and the Japanese had to fight in the 51's favorable performance envelope. The toughest fighter battles usually occurred during interdiction or strike missions when the 51s were necessarily at low level, where the enemy aircraft performed best.

Always fuel conscious, the Mustangs "coasted in" at a fairly high throttle setting to keep their spark plugs clean and the aircraft in fighting trim. The pilots wanted the fuselage tank below 40 gallons remaining because in a steep turn, shifting fuel weight could cause control reversal and the aircraft tried to snap-roll. As a general rule, the 51s escorted and fought on the fuselage tank if they had to jettison the drop tanks. When the fuselage tank ran dry it was time to think about heading home, as wing internal tanks would provide a bit more than was needed to return to Iwo. Later experience showed that the Mustang could perform well in combat with drop tanks attached, fight with the remaining fuselage tank fuel, then switch back to externals if they were still attached.

To some pilots, the 20 to 60 minutes over Japan was just the thing to shake off the lethargy of the long flight from Iwo. Harve Phipps said, "I think the combat break midway in the mission served to stimulate you enough that you didn't get bored. The main problem was the cramped space for the time involved."

For the return flight, "We dropped our tanks, shot up all our ammo and tested the relief tube," Harry Crim explained. "We set the rpm on about 1 800 with full throttle at 10,000 feet, pulled the mixture back until our wingman signaled the coolant shutter was coming open, then eased it forward just a tad. This setting worked like a charm, though the mixture control was set up to fly only in selected places. We would indicate about 210 and burn about 40 gallons per hour. This would burn up a set of plugs but it didn't seem to bother the engines."

Crim tells what it was like southbound from Japan: "Suddenly you realize that you are extremely fatigued, you are thirsty, and almost unable to fly the plane. The parachute harness irritates your neck, the sun is too hot, and worst of all you discover you are 'butt sprung.' There is no position in which you can get rid of the ache in your sitting apparatus for longer than a minute or two. You let the air out of your seat cushion and it feels wonderful, then the ache returns. You let the air back in the cushion and you're fine again, for a minute. After awhile you exercise some Cod-given power to just ignore it.

"Now you pass Kita Jima, 40 miles to go and then there is Iwo. You revive yourself enough to land and taxi your airplane in, wave to your crew chief, resolve to jump out to show what a hardy fellow you are, but after releasing the harness you can't raise yourself. So I sat there for awhile filling out the forms, telling the crew chief how we fared and then tried again; no luck. About this time the flight surgeon's helper crawled up on the wing with a shot of mission whiskey.

"Ah, here's the thing for quick strength, so I took the two ounces and downed it like WW I pilots and cowboys are supposed to do. No luck; all I did was get sick. So I graciously allowed Sgt. Pesci, my crew chief, to lift me out of the cockpit and help me to the ground. A little walking around and I revived enough to be self-mobile." For obvious reasons, Crim named his Mustang "My Achin'" with what is politely described as a mule painted below the legend.

Crim's description explains why VLR pilots were rotated after barely 100 hours of combat—half the normal tour for an ETO fighter jock. It also demonstrates why the Iwo Jima fliers would rather take on Japanese fighters at odds of six to one than fly an aborted mission. The regulations called for 15 completed VLRs. Crim, for instance, flew 1 8 plus three aborts.

Of those 1 8 missions, only six were escorts. The others were strike sorties which largely involved shooting up enemy airfields, sometimes with five-inch High Velocity Aerial Rockets. Six HVARs added over 700 pounds to takeoff weight — something not appreciated by the pilots, but they packed a tremendous punch, particularly against shipping and reinforced buildings.

There were generally two coast-in points for sweep-strike missions. One was at a point of land 50 nautical miles east of Tokyo called Inubo-Saki. The other, more circuitous, route was 50 miles north of Inubo-Saki, at Kawagaro. The latter allowed the 51s to enter the Tokyo area from the northeast, an unexpected direction.

There were generally two coast-in points for sweep-strike missions. One was at a point of land 50 nautical miles east of Tokyo called Inubo-Saki. The other, more circuitous, route was 50 miles north of Inubo-Saki, at Kawagaro. The latter allowed the 51s to enter the Tokyo area from the northeast, an unexpected direction.

The first strafing mission was flown April 16 against Japan's largest airfield, Atsugi. But the 51s were diverted in a hustle change to Kanoya and in the confusion and poor visibility only 57 of 108 Mustangs attacked. Later missions were more successful, and from April 7 to June 30, Seventh Fighter Command claimed 666 e/a destroyed or damaged—mostly on the ground. The first week of July brought claims for another 75 destroyed or damaged. Most claims were verified by gun camera, and thereby hangs a tale. Taken aback by the dramatic success of the Navy's carrier warfare documentary film "The Fighting Lady," the Air Force provided 7th F. C. with color gun camera film. Processing was done by Kodak, Hawaii, and before the war ended the folks back home were treated to some spectacular films, courtesy of Mickey Moore's pilots.

Low-level strafing lent itself to pyrotechnic movie footage, and the Iwo pilots had their own system. The technique of strafing airfields was to put a squadron in close line astern at 1,500 feet, indicating 200 mph. When the last flight leader was abreast of the field he called for a 90-degree turn towards the target. Each pilot then flew low across the field, shooting anything which appeared in front of him. At less than 200 mph there was time for steady aiming, and the sheer volume of fire from 16 Mustangs (96 guns) was often enough to suppress all flak. "You could really put a lot of ammunition into a place," Crim remarked.

Once across the field the 51 s stayed low until about two miles out, then turned line astern again and reformed into flights. It was a cardinal sin in the strafer's bible to make a second pass at the same target, so each flight usually selected targets of opportunity and set course for the rendezvous.

As related before, many strafing parties turned into violent low-level dogfights. On July 8 a large enemy gaggle bounced strafing Mustangs near Tokyo and in the ensuing battle downed seven for the loss of five. But the 51s more than evened the score by claiming 45 e/a destroyed on the ground.

Harry Crim became Seventh Fighter Command's third ace during a strafing mission on July 1 when he shot down a stray Betty bomber. He also destroyed a George fighter on Namamatsu Airfield. His third and fourth kills had come on May 29 during an escort to Yokohama when, with no appreciable aerial opposition, his squadron was fat with fuel due to prolonged low power settings. "We were patrolling for about an hour and 20 minutes so each squadron leader took his people off to hunt," after the B-29s departed. Crim's former outfit, the 72nd F.S., was strafing a field north of Tokyo Bay when six Zekes saw them. "We caught up with the Zekes about the time they caught up with the 72nd," Crim recalled. He killed one Zeke and then saw another chasing a 51 in a circle. Both aircraft were "pulling big Gs at about 3,000 feet, with real pretty vapor streamers." Crim nailed the Zero with two bursts, watching the Japanese bail out. But the 72nd pilot was angry because he said that in two more turns he would have had the kill. "So goes the war," Crim reflected philosophically.

Airborne targets were pretty scarce after the end of May, and many pilots never saw a dogfight, let alone participated in one. It was particularly tough on the 506th group, which had a late start. But on two missions in early June the group escorted B-29s to Osaka and Tokyo, losing only one 29 while claiming a total of 11 confirmed, four probables and two damaged on the 7th and 10th. For this accomplishment the 506th was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation. The group encountered aerial opposition on only four other occasions, for a wartime total of 25 planes shot down.

Eighteen years later Aust's cousin, serving in the Air Force, found a grave marker at almost the exact location the P-51 pilot had last seen the second Zeke. The date on the marker was August 10, 1945. This was proof enough, and Abner Aust officially joined the ranks of the fighter aces.

The top scorer of Seventh Fighter Command was Captain Robert W. Moore, a Kentuckian with the 15th Group's 45th squadron. He finished the war with a total of 12 victories. Jim Tapp's final score was eight, then came Harry Crim with six. But Major John W. Mitchell, also of the 15th F.G., had the longest war. Originally a P-38 pilot in the 339th F. S. at Guadalcanal, he ran up six kills in 1942-43 and led the famed Yamamoto Mission. The indefatigable Mitchell added five more victories over Japan and was back at work in Korea, notching four MiGs. The common factor in all these aces' careers is that each was a squadron or flight commander, giving them the initiative required to pay off on each scoring opportunity.

In July, the last full month before the Japanese agreed to unconditional surrender, the Iwo Jima fighter groups received some P-51D-25s as replacement aircraft. Many of these had the lead-computing K-14 gyro gunsight in place of the old N-9 which required a good deal of skill and "Kentucky Windage" in making deflection shots. The K-14 required a smooth touch on the controls to be truly effective, but was deadly accurate in nearly any tactical situation. It could only be defeated if the target aircraft rapidly reversed its turn in a curving combat, momentarily tumbling the gyros when the P-51 attempted to follow.

One 21st group pilot familiar with the K-14 was shot down and captured by the Japanese. Under standing authority from intelligence officers, captured airmen were allowed to divulge almost any information which would ease their situation, and the 21st pilot explained about the K-14.

The Japanese took this information as a lesson learned, but the tale has an ironic and—to the Mustang pilots—a humorous end. In one of the last large dogfights the Mustangs fought over Japan, at least eight Franks were shot down because their pilots assumed all P-51s now had the K-14 when actually only a relatively few replacement aircraft had the lead-computing sight. When the Franks reversed their turns to topple the K-14 gyros they presented their pursuers with a brief no-deflection shot for which the N-9 was ideally suited! Had the Franks kept turning in their original direction they would have stood a good chance of outmaneuvering the 51s.

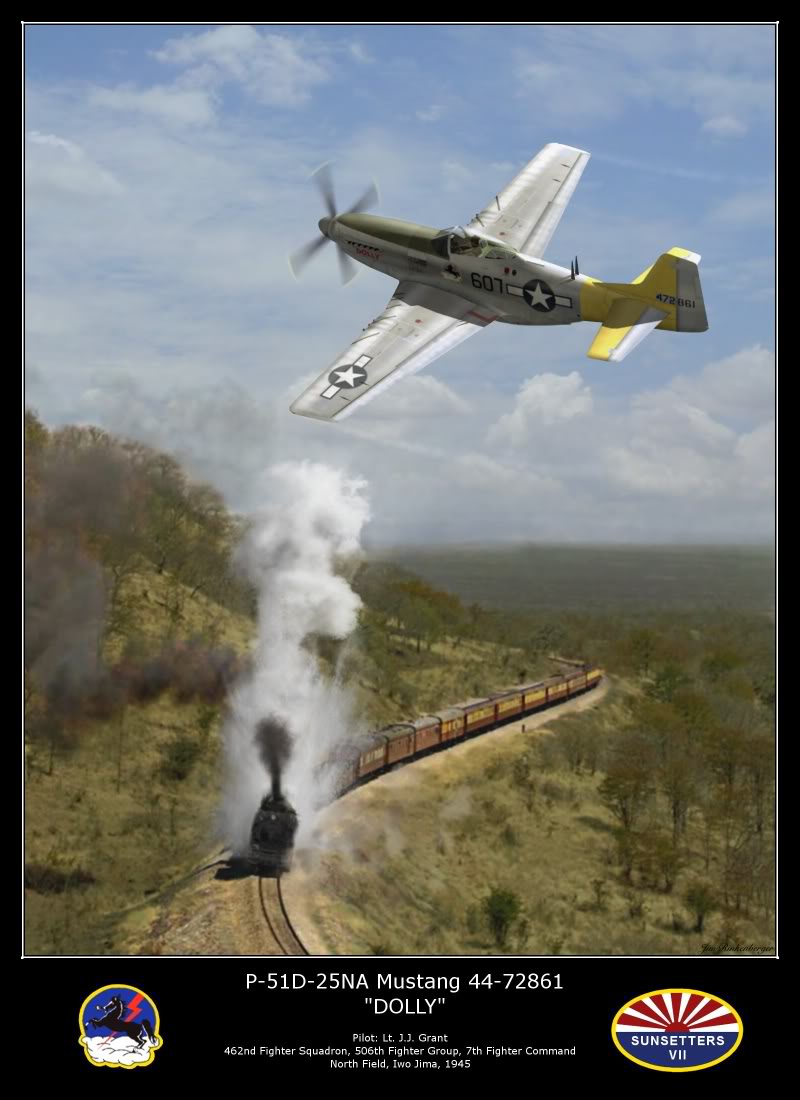

In the last days of the war, with cruise control perfected, the Mustangs lingered longer than ever over the Empire. P-51 s ranged from the Chosie Peninsula north of Tokyo clear south to Kyushu. More shipping was attacked, but an increasingly favorite sport was "train-busting." This popular pastime had previously been limited almost entirely to ETO pilots, as railroads were naturally few and far between in the Pacific. Shooting a locomotive full of holes, watching steam and spray geyser high in the air, gave a fighter pilot a thrill which other targets just didn't generate.

The last VLR was a B-29 strike on Osaka's airfields; a seven hour, 1 5 minute job for the Mustangs on August 14. "We had just come back to rendezvous after the strike when the news of the peace feeler was relayed by the B-29 of our navigation group," Harry Crim recalls. When we returned to base we were immediately put on maximum alert with a strike mission scheduled for the next day. It was called off about noon and we were alerted for one the next day. This repeated until September 2. (The date the Japanese signed the formal surrender.) On that day General Moore departed Iwo for Washington, D.C. in an LB-30. I was on board."

Acknowledgments: Special thanks and appreciation is extended to Col. Harry C. Crim, Jr., USAF (Retired) for the exceptional amount of information and photos made available for this project. Other Sunsetters contributing important material were Maj. Gen. Ernest M. Moore, USAF (Retired), Mr. Harve H. Phipps, Jr. and Mr. Neil T. Smith, Jr.

Arrival time: 1/17/2026 at: 1:14:52 AM

Home | Reunions | Contact Us | VLR Story | Mustangs of Iwo Jima | Combat Camera Footage | Battle of Iwo | 457th | Webmaster ©506thFighterGroup.org. All Rights Reserved. |